You may be a businessman or some high-degree thief

They may call you doctor, or they may call you chief, But you have to serve somebody… Bob Dylan

No matter your role, you are accountable to someone. As we ascend the organizational ladder, stakeholder management becomes an increasingly more critical skill.

Stakeholder management is the ongoing process of identifying, evaluating, and engaging the people who are critical to our success. Stakeholders are broadly defined as anyone impacted or interested in our projects or business operations. Their perceptions often determine the outcome of our efforts; therefore, managing these expectations is vital.

We must balance the needs of our constituents with our capacity to fulfill them. In this article, I share practices and tools to identify and evaluate the needs of our stakeholders. This allows us to develop a strategic focus on the people and issues that require our attention.

Identify Stakeholders

Contents

We should regularly survey the environment to refresh our stakeholder registry. We need to cast a wide net to collect those directly, indirectly, or are perceived to be affected by what we do.

We commonly limit the focus on the obvious stakeholders—team members, managers, and regular customers. Brainstorming sessions can expose less apparent candidates, as will analyzing our project and organization’s documents.

Once we have created this initial cohort, we should explore radiating concentric circles of adjacent groups. The SIPOC framework (Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Output, Customer) can help us broaden our search.

A transportation project, for example, will have many layers of stakeholders, including local, state, and federal government authorities, as well as citizens directly benefiting or adversely impacted. The radiating circle may extend distant localities whose projects were not chosen. The SIPOC analysis will remind us to include vendors, suppliers, and less apparent affected entities.

Categorize Stakeholders

Depending on the project size, there may be hundreds or even thousands of stakeholders. To effectively manage these numbers, we should categorize them into cohorts.

For small projects, grouping based on a simple set of attributes may be sufficient, such as:

- Internal vs. external;

- Organizational unit, location, or customer type; or

- Level of impact or required level of engagement.

Complex classifications can include detailed multivariate analysis of the impacted constituencies. The Purple Line light-rail project outside Washington, DC, commissioned a comprehensive review of the demographic, employment, and travel behaviors of residents and businesses along the corridor.

These analyses can be the basis for developing user personas. Personas are fictional characters that bring these composite stakeholders to life for the project team. The characters are posted on the team room walls as a reminder of whom we are serving.

Power vs. Interest Mapping

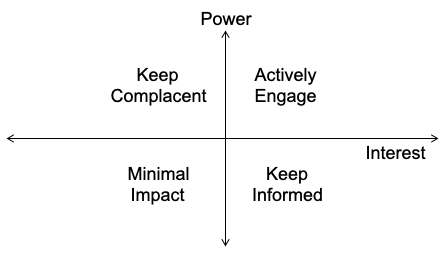

The Power/Interest Mapping (PIM) is a tool for understanding stakeholders and how to engage them on our projects. Based on this mapping, we can categorize the stakeholders into:

- Actively Engage. Stakeholders with high-power and interest are the most important. This includes the project sponsor, senior management, and key customers;

- Keep Complacent. Stakeholders with high-power and low-influence have formal power, but may not be very interested in all project aspects. We should focus on addressing their specific, niche needs;

- Keep Informed. Stakeholders with high-interest but low-power are often those directly affected by the project. These stakeholders have the potential to either promote or impede our progress;

- Minimal Impact. Those with both low-power and -interest are still stakeholders that require the least amount of attention.

The mapping helps us identify the most critical stakeholder and focus our attention on them. The model will also serve as an initial filter for the subsequent analyses.

Stakeholder Engagement Assessment Mapping

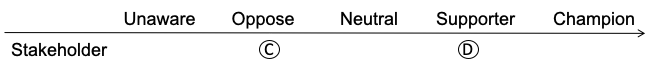

The Stakeholder Engagement Assessment Matrix (SEAM) allows us to consider our stakeholders with their current versus desired perspectives on our work. Conducting the SEAM analysis requires that we ask the uncomfortable question: do our stakeholders support or oppose our efforts?

The best way to assess our stakeholders’ perceptions is to meet with them to discuss their concerns. Then we can determine what they want from us and what we need from them.

Combining the SEAM and PIM analyses identifies those stakeholders that require the most attention. A critical stakeholder (H/H) that opposes the project will need more attention than one that is currently a champion. We may choose to invest less energy in non-critical stakeholders that are at least neutral to our efforts. Triaging, our level of engagement allows us to focus our attention strategically.

Stakeholder Relationship Modeling

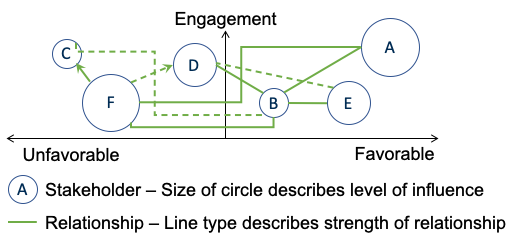

Organizations are complex organisms. The Stakeholder Relationship Model (SRM) integrates a relationship analysis with the other tools. Understanding levels of influence and the relationships among critical stakeholders is a force multiplier. We can leverage our supporters to influence their colleagues.

The analysis requires substantial effort and may be reserved for understanding the inter-relationships among critical stakeholders. The tool can also be used to evaluate how to influence decision-makers for a specific issue.

In the Model, we start by assessing stakeholder perspectives along the horizontal, favorability plane leveraging the SEAM analysis. We then consider the vertical (engagement) dimension. Engagement may be a combination of the PIM as well as other observed behaviors.

Then, we assess the size of the stakeholders’ influence. Circle size denotes the degree of influence. We should consider both formal and informal forms of power. Executives exercise formal power and will have larger circles that associates. People with strong relationships or expertise may exert informal power that is greater than their place in the organization’s hierarchy.

Then, we assess the size of the stakeholders’ influence. Circle size denotes the degree of influence. We should consider both formal and informal forms of power. Executives exercise formal power and will have larger circles that associates. People with strong relationships or expertise may exert informal power that is greater than their place in the organization’s hierarchy.

Lines represent both the strength and direction of the stakeholder relationships. Solid or thicker lines depict a more robust connection than dotted lines. Arrows indicate the direction of that relationship.

Putting this together creates a visual representation of organizational dynamics and opportunities for overcoming challenges, in our example:

- A manager (F) may exert formal power over their direct reports (C, D), which is depicted by the size of the circle, the solid line, and the direction of the arrow. Changing the manager’s perspective will impact their team;

- Nearly every organization has a central player (B), who is connected to everyone else. This person can play a pivotal and influential role—make them an ally;

- We might enlist the executive (A) support to overcome the resistance of the manager (F).

We can become more effective managers and project managers by using these stakeholder management tools. They will help us pinpoint where we should expand our efforts. Who needs to be influenced, and what relationships can we leverage? Employing these tools takes effort but pays large dividends.

© 2020, Alan Zucker; Project Management Essentials, LLC

To learn more about our training and consulting services, or to subscribe to our Newsletter, visit our website: www.pmessentials.us.

Related Project Management Essentials articles:

- Engage Your Stakeholders

- Know your Stakeholders

- Stakeholder Management: A Key to Project Success

- Successful Projects: What We Really Know About Them

Image courtesy of: thediwire.com