Project management relies on metrics to chart and manage performance. Good metrics are valuable. They measure the right things and provide the project manager, team, and stakeholders with actionable information. They also support and reinforce constructive team behaviors. By contrast, bad metrics can lead the team astray and waste effort. Effective project managers understand the importance of good metrics and thoughtfully select the right ones to employ.

“…not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” – William Bruce Cameron

Last month, in Project Status is Subjective—Part 1, I presented how linguistic and cognitive bias influences status reporting. In this article, I show that status metrics are also subjective and provide recommendations to improve their use.

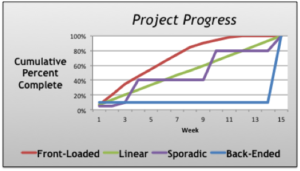

Underlying many project metrics is the assumption that progress is proportional. For example, if you can pave one mile of road a day, in 10 days 10 miles should be complete. Software development and most other projects do not really conform to such a predictable path. The complexity of the tasks, resource capacity, and individual work patterns can affect the pace of reported progress.

The college term paper demonstrates how students can follow different progression paths and still be successful. We typically observe the following performance archetypes:

- Front-Loaded: Students that complete the assignment weeks before it’s due. In school, these students are often called “over achievers” and are praised by their teachers. However on a project, these workers may be criticized for padding their initial estimates.

- Linear: Students that begin the paper immediately and advance at a regular pace. These “Steady Eddies” make “good” progress. Typical project status metrics reward this performance.

- Sporadic: Students that exhibit bursts of activity. They may work many hours one week and none the next depending on their capacity. Sometimes they will appear to be behind schedule and at other times appear to be ahead. Generally teachers worry about these student’s because they don’t seem to “consistently apply themselves.” While this pattern best represents how most projects actually progress—with peaks and valleys of advancement—most project managers are uncomfortable with this unpredictable progress.

- Back-Loaded: The procrastinators will complete the paper in the last week of the semester. They will be “behind schedule” for the entire term. They are criticized for their seeming lack of progress and labeled “slackers.” Project managers similarly worry about back-ended progress even though there is a growing body of evidence that procrastinators are more creative and thoughtful. (See: Adam Grant’s Why I Taught Myself to Procrastinate)

How we measure and label progress impacts team behavior and organizational culture. People will seek praise and generally strive to report good or on–track performance. Often the incentives to appear on-track outweigh those of being transparent and open about actual progress or impediments to progress.

“What gets measured gets managed.” – Peter Drucker

I have observed teams engage in destructive activities to avoid criticism and blame. One team was trapped in a wasteful, continuous re-planning effort—moving complex work to later project phases—just to maintain their on-track status. This maneuver created temporary relief, but eventually blew up when they ran out of work to defer and needed to deliver the final product.

Project managers that recognize and accept that status reporting and metrics are subjective can leverage this knowledge to more effectively manage their projects. Below are four recommendations:

Identify Metrics that Support the Project Goal

Contents

The first step is articulating the project’s goal. Good project goals, like performance goals are specific, measureable, and time bound. Good metrics:

- Support the goal,

- Provide valuable and actionable insight to the project’s progress, and

- Incent constructive behaviors.

Valuable metrics measure progress toward the goal. If you are developing software, measure things that relate directly to the delivery and quality of the product. For example: How many function points or story points have been delivered? How many critical defects remain to be remediated?

Traditional metrics tend to measure volume: How many lines of code were written? How many test cases have been executed? Or, how many test cases have passed? They do not tell you if good code was written, or if critical issues were identified.

Many metrics are also based on performance against the baseline project plan and cost estimate. These metrics rely on the critical assumption that the plan is right. As the German military strategist, Helmuth von Moltke, said, “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.” Like battle plans, most project plans do not adapt to changing circumstances and are out of date shortly after the project starts.

Agree on the Metrics

Once the metrics have been identified, have the team and stakeholders agree to them. Agreement ensures:

- The team and stakeholders support the metrics,

- The metrics are fair and promote constructive behavior, and

- The metrics contribute to the success of the project.

Use Simple Metrics

All project participants need to understand the rules for calculating the status metrics. Use the 5-Year Old Rule; simple rules provide transparency and clarity. Complicated rules shift focus from actual project performance to the metric’s calculation.

I once worked with an organization that had an extremely complicated algorithm for calculating the red/amber/green schedule status indicators. It was so complicated that long, supplemental reports were required for project managers to determine what drove the color. Executive stakeholders were unable to decompose the metrics to understand what was happening and what needed to be done. These rules were eventually abandoned.

Apply Metrics Consistently

Consistent application of good metrics encourages constructive, normative behavior. Metrics set priorities and reinforce the expected performance and conduct. When expectations are clear and applied consistently, the team is more likely to be successful. Conversely, constantly shifting metrics and expectations promotes reforming and storming behaviors.

Status reporting is an ever-present part of project life that is not often examined. The way we choose to report status, select metrics, and measure performance has a profound impact on the team and how we view the project’s progress. Metrics that measure what is important and promote productive, team behaviors are valuable management tools.

© 2016, Alan Zucker, Project Management Essentials, LLC

Sources:

9 Albert Einstein Quotes That Are Totally Fake. (n.d.). Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/9-albert-einstein-quotes-that-are-totally-fake-1543806477

En*theos. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2016, from https://www.entheos.com/quotes/by_teacher/peter%20drucker

Grant, A. (2016, January 16). Why I Taught Myself to Procrastinate. Retrieved January 31, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/opinion/sunday/why-i-taught-myself-to-procrastinate.html?_r=0

“No Battle Plan Survives Contact With the Enemy”. (n.d.). Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://www.lexician.com/lexblog/2010/11/no-battle-plan-survives-contact-with-the-enemy/

Zucker, A. (n.d.). Project Status is Subjective—Part 1: Linguistic and Cognitive Bias. Retrieved February 26, 2016, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/project-status-subjectivepart-1-linguistic-cognitive-bias-alan-zucker?trk=prof-post