I believe each of us has our own, undiscovered inspirational story. We have not recognized our own accomplishments. We have not verbalized our achievements into a personal narrative. Or, we may be uncomfortable talking about ourselves.

We consider heroes or great people to be innately different from ourselves. They were destined for greatness. Or, had special training or opportunities. They are braver, stronger, or have a greater abundance of natural abilities.

In reality, we all have achieved great things. We have overcome challenges or difficulties. We have demonstrate integrity, courage, and bravery. We have succeeded beyond our expectations. We simply have not expressed or shared them.

We can use our stories to build our confidence and acknowledge our value and self-worth. Through our stories we can share our values and beliefs. We can impart our experience and wisdom. We can motivate others.

There are professional storytellers. But this is not a guild profession. Ordinary people tell their stories on podcasts and broadcasts, like The Moth. What separates them from the rest of us is that they are willing to share.

I have a friend who I consider to be is a wonderful storyteller. She writes beautifully. She teaches writing in college. Yet despite my encouragement, she is not comfortable telling her stories publicly.

Storytelling is universal and integral to civilization. The oral tradition pre-dates written stories by thousands of years. Some cultures, like the Native Americans, had no written language and have relied on stories as their primary form of remembering and communicating their heritage and beliefs.

In contemporary society, storytelling lives on. The tradition is often associated with the South. Stories figure prominently in American society. They are used to sell products. Candidates put their personal narrative at the center of their political campaigns because likeability is more important than issues. Stories create and foster corporate cultures.

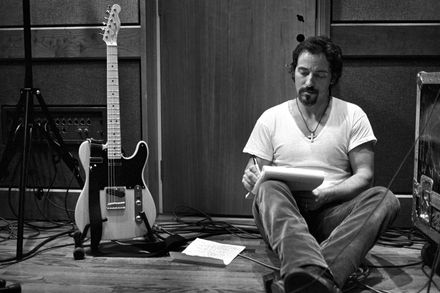

Bruce Springsteen and Steve Jobs are legendary storytellers. Springsteen tells stories through his songs and weaves his own personal narrative into his concerts. Steve Jobs used evocative imagery to sell Apple products. Apple’s 1984 Super Bowl ad introducing the Macintosh is legendary.

The Modern Inspirational Stories

Modern, inspirational stories generally come in one of two forms:

- Challenge-to-triumph, or

- The transformation.

In the challenge-to-triumph story, the protagonist is confronted with adversity. They overcome this challenge and become stronger or better afterwards. The tragedy is often an ailment, disability, a tragic event, or other life hurdle.

Lance Armstrong is an example of the challenge-to-triumph story. Armstrong overcame testicular cancer to become a 7-time winner of the Tour de France. His physical rehabilitation, his tenacity, his ability to overcome cancer was legendary. This triumph was embodied by the Live Strong campaign. Over 80 million people wore those yellow, rubber bracelets to support the cause and identify with his triumph. Sadly, this legend was shattered when Armstrong was stripped of his victories due to blood doping.

In the transformational narrative, the protagonist metamorphoses into someone special. The transformation can be the result of a single event; or more often through diligent effort that culminates a new or special status or position. The transformational story primarily differs from challenge-to-triumph in that the character does not confront a dire event as a precursor to the ascent.

During live versions of “Growing Up,” Bruce Springsteen shares that his ascent to stardom was a long road and not at all preordained, “There I was, just a normal guy. And, there I was the next day. And, I was still just a normal guy.” Springsteen spent years toiling as a bar-band musician before achieving fame.

Sheryl Sandberg’s ascent to becoming the chief operating officer at Facebook was the culmination of a long path. Before becoming the chief operating officer at Facebook, she had a distinguished career. She had high-ranking roles at the World Bank and U.S. Treasury before moving to Silicon Valley.

Based on their difficult childhoods you would not expect that Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, or Barak Obama would become President of the United States. One of the political gifts they shared is the ability to tell a good story. Bill Clinton was the man from Hope, Arkansas; and he exploited that play on words to his advantage.

Craig Blackburn has an inspirational story. He is a person with Downs Syndrome. He used to work as a bagger in a grocery store. Now he lobbies Congress on behalf of people with disabilities and is motivational speaker.

The Art of Story Telling

No story comes out perfectly the first time. Jack Kerouac, the Beat writer, was mythologized to have written “On the Road” on a giant roll of teletype paper in a 3-week fury. In fact, he followed the traditional path working through drafts and honing the story over many years. In a similar vein, Jerry Seinfeld still goes to comedy clubs just to perfect the delivery and timing of his material.

A good short story is comprised of six elements:

- Theme. What is message? What do you want the reader to know or learn?

- Conflict. What is the central issue of the story? What does the protagonist want and how will they achieve it?

- Plot. What are the events in the story? What happens to the main character?

- Character(s). Who is the main character or characters? Who supports the main character in thir journey?

- Setting. Where and when does the story takes place?

- Point of View. What is the perspective and voice of the storyteller?

The role of the storyteller is to weave these elements into an inviting narrative. All stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end. The beginning sets the stage. The middle develops the plotline. And, the end closes the story.

Think back to our childhood fairy tales. The all started with, “Once upon a time.” The primary characters are introduced. The setting is described. The primary conflict is presented.

Once upon a time a very poor woodcutter lived in a tiny cottage in the forest with his two children, Hansel and Gretel. His second wife often ill-treated the children and was forever nagging the woodcutter. There was not enough food…

The endings were often similarly formulaic, “and they all lived happily ever after.”

Your stepmother is dead. Come home with me now, my dear children!” The two children hugged the woodcutter. “Promise you’ll never ever desert us again,” said Gretel, throwing her arms round her father’s neck…And they all lived happily together ever after.

The middle of the story conveys the salient facts needed to draw us in and explain what happens to the characters. In Hansel and Gretel, we learn about their trip into the woods, the wicked witch, and how they outsmarted her.

Your Inspirational Story

Not long ago, I delivered a workshop at a project management conference. One of the other keynote speakers talked about his cross-continent bicycle ride. Through this, I realized that my bicycle rides, though shorter, were still a good tale.

My son is a paratrooper in the Israeli army. When he was just 13-years old, I took him on a week-long bicycle ride across Israel…

For your inspirational story, start small.

We all have great stories. However, finding them is not always easy. It requires us to pause, contemplate, and recognize our special traits, endeavors, and accomplishments. Becoming a storyteller requires time and dedication to the craft.

To find your inspirational story start with an inventory. Consider your life. What are your achievements? What hurdles have you overcome? What are you proud of? At this point, don’t form a story. Just identify the events. Write each one down on a separate index card.

Go through the index cards. Sort them on flat surface. Which one draws your attention? Which generates emotional energy—either positive or negative? For your first story, pick the one that that draws your attention. Don’t be too choosy. You will have many opportunities to tell your life stories.

Once you have selected your story, start working through the elements. On separate index cards, start writing notes for each of the areas:

- Conflict andTheme. Reflect on the events. Why do you want to tell thisstory? What do you want your audience to learn or know? These are the most important elements of your story. So, you told a great story, but what is the takeaway or the message? What should people do after hearing it?

- Character(s). Who is the main character? Most likely it will be you or someone you know well. Who are the supporting characters? Often the smaller the supporting cast, the better.

- Setting. What is the place and time of the story? If these details do not materially add to the narrative, leave them out.

- Point of View. Most stories are either told in the first- or third-person voice. Be sure to use the active rather than the passive voice. In other words, “I did…” or “She did…” Not, “It happened…”

- Plot. What are the details and key events in the story? Be parsimonious. Many beginners introduce unnecessary details.

Start sketching out your story. Write out an index card for each section of the story. For each card, write down the plot element. Who are the active characters? What is the setting? What happened?

Even though we intend to orally tell our stories, we want to write out the roadmap. By writing the elements, we begin the process of building our story—card-by-card. We can see and touch the components, making it easier to review and revise them.

Begin to practice you story. Often the beginning is the most important section. Get people hooked in the first few sentences. I have a friend who was a Navy SEAL and had great stories. He often starts with, “Did I ever tell you about the time, I was in…”; then mentions a hot spot like Lebanon or Somalia.

Practice your plot points. Consider whether they add to the theme of the story. Often, we add facts that actually detract from the overall storyline.

Use your stories at work or with your family. Watch you audience. Solicit feedback. Was your story effective? Did it communicate the message? If not, continue to hone the material.

If Springsteen and Seinfeld continuously practice and refine their craft, so can you.

© 2018, Alan Zucker; Project Management Essentials, LLC

To learn more about our training and consulting services, or to subscribe to our Newsletter, visit our website: www.pmessentials.us.

Image courtesy of: David Rose, RollingStone.com

2 thoughts on “Our Own Inspirational Stories”

Comments are closed.